Cult vs Religion: A Comparative Analysis

“The only difference between a cult and a religion is the amount of real estate they own” ~Frank Zappa

‘A man with a conviction is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point. We have all experienced the futility of trying to change a strong conviction, especially if the convinced person has some investment in his belief. We are familiar with the variety of ingenious defenses with which people protect their convictions, managing to keep them unscathed through the most devastating attacks. But man’s resourcefulness goes beyond simply protecting a belief. Suppose an individual believes something with his whole heart; suppose further that he has a commitment to this belief, that he has taken irrevocable actions because of it; finally, suppose that he is presented with evidence, unequivocal and undeniable evidence, that his belief is wrong: what will happen? The individual will frequently emerge, not only unshaken, but even more convinced of the truth of his beliefs than ever before. Indeed, he may even show a new fervor about convincing and converting other people to his view’.

~Leon Festinger (Social-Psychologist)

INTRODUCTION

Sam Harris described Christianity as a “cult of human sacrifice”.[1] But what are the differences between a religious cult and a religion? Essentially, the differences between the two are superficial and predominantly discursive in nature. Pavlos defines a religious cult in the following words:

‘A religious cult is a religious group whose leader formulates the group’s dogma and isolates the members from others who would normally support their original beliefs. Members become dependent on the cult for the satisfaction of their needs. The cult leader gains absolute control over the behaviour of members … cults are identified as deviant religious groups whose members are generally labeled by the noncult community as religious “kooks” or “crazies”.[2]

This definition could, in essence, be applied to the Christian religion. The primary hurdle in applying this definition is that it appears to imply the corporeal presence of the cult leader. However, such a hurdle may be overcome, or at least partially mitigated, by substituting the cult leader with the congregation leader, or by applying the definition to the birth and early stages of the Christian religion, when the founders, Jesus and Paul, were allegedly walking amongst their relatively small group of followers.

This essay will critically apply Pavlos’ definition of religious cult to two popular cults in the United States: the Branch Davidians and Heaven’s Gate. Some of the social-psychological implications of the features of cults identified by Pavlos will also be briefly discussed. Finally, Pavlos’ definition of ‘cult’ will be interpreted in such a manner as to apply it, albeit comparatively loosely, to the Christian religion. To ensure a thorough comparison of Pavlos’ definition with Heaven’s Gate, the Branch Davidians and the Christian religion is achieved, it will be broken-down into the following six elements:

Religious Group

Leader Formulates Group’s Dogma

Isolation

Dependency

Behaviour Control by Group Leader

Group Labelled as Deviant by Outsiders

RELIGIOUS GROUP

To begin, a workable definition of ‘religious group’ must be established. Bezdek provides the following sociological definition of the term ‘group’: ‘The term ‘‘group’’ can refer to small, face-to-face groups or large, formal organizations. Collectivities, a third type of group, are defined by observable attributes (such as race or age), or by common interests…’[3] Thus, a religious group may be defined as a small or large collective of people who share common religious beliefs and who practice some common religious rites and rituals.

THE BRANCH DAVIDIANS

The Branch Davidians are one of the offshoots of the Seventh-day Adventist Church.[4] The Seventh-day Adventist Church have their origins in the “Great Disappointment” of 1844.[5] The “Great Disappointment” refers to William Miller’s failed prophecy of Christ’s return. Miller’s followers were known as Millerites.[6] As a result of this disappointment, numerous Christian sects emerged with new eschatological interpretations of the book of Revelation, which eventually sowed the seeds for the rise of the Branch Davidians.[7] The Branch Davidians are most popular for the Waco Siege in 1993, in which eighty cult members, including cult leader David Koresh, were killed.[8] The Siege at the Branch Davidians’ compound played into the group’s eschatology, with the cult convinced that this was their End-times battle with the “Babylonians”/”Satan”, as vaguely and ambiguously enunciated in the book of Revelation.[9] There is little doubt that the Branch Davidians qualify as a religious group, for they are a religious collective who were, and remain to this day(‘New Davidians’),[10] isolated both ideologically and spatially from not only other sects and denominations within Christendom, but from the outside world in general.

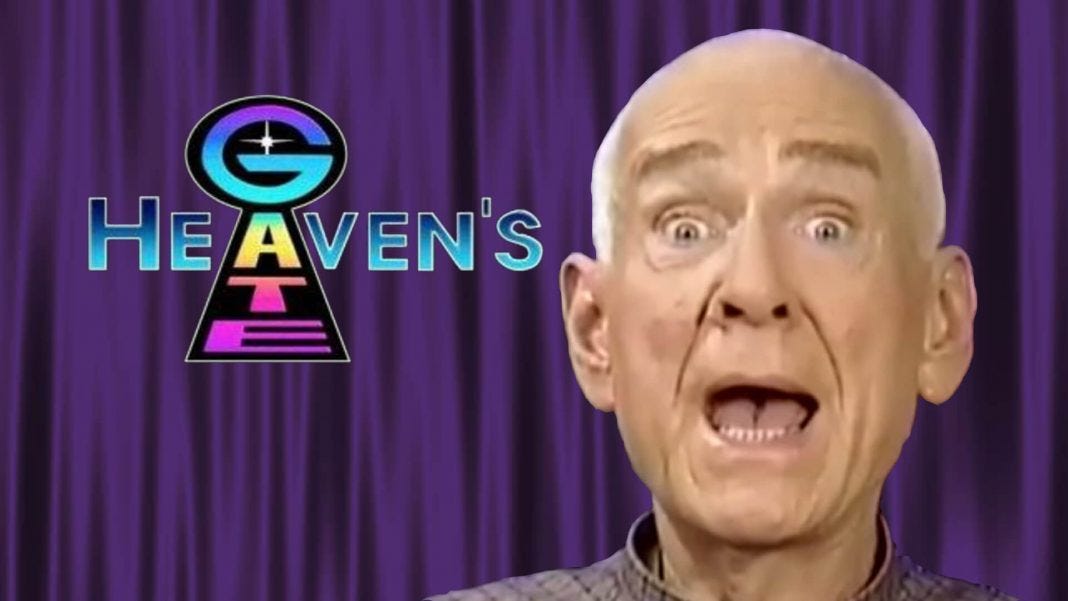

HEAVEN’S GATE

Heaven’s Gate was founded by Bonnie Lu Nettles and Marshall Herff Applewhite, Jr.[11] Applewhite and Nettles both came from Christian backgrounds [12] and Christianity was a significant unifying and underpinning theological foundation for Heaven’s Gate.[13] Influenced largely by Nettles, the ideology of this religious UFO cult was also heavily influenced by Theosophy, Gnostic Christianity, the New Age Movement, Ufology and a strange metaphysical brand of Darwinian evolution.[14] This cult is most famous for the ritual suicide of 39 of its members in 1997, who all believed that they were evolving to the ‘Next Level’, and that they were going to ascend into Heaven on a cloud, as per the book of Revelation.[15] The cloud from the book of Revelation was interpreted by the cult as being an alien spaceship.[16] As with the Branch Davidians, the group’s religious ideology was heavily influenced by Christian eschatology, and again largely from the book of Revelation. Also, in similitude to the Branch Davidians, Heaven’s Gate was a collective of believers who lived in isolation from the outside world.[17] Thus, it is clear that Heaven’s Gate was a group. The cult’s set of beliefs, whilst deviating in many respects from many denominations of modern, mainstream religion, were very religious. The cult believed, in accordance with Nettles and Applewhite’s teachings, that ‘Jesus Christ [was] an individual of that ‘Next Kingdom,’[18] that Nettles and Applewhite were ‘the ‘Two Witnesses’ described in the book of Revelation’,[19] and in typical Gnostic Christian fashion, that education not faith was the key to salvation.[20] Hence, although Heaven’s Gate was essentially a UFO cult, they may be safely classified alongside the Branch Davidians as also being an eschatologically-focused religious cult, whose beliefs and practices derived from an identifiable religious core.

LEADER FORMULATES GROUP’S DOGMAS

In both Heaven’s Gate and the Branch Davidians, the leaders were the ones who established the dogmas which dictated the beliefs and practices of their respective cults. With regards to the central dogma of Heaven’s Gate, Cowan and Bromley say:

‘Applewhite and Nettles followed in the footsteps of many religious leaders and asserted that the majority of religious traditions have misunderstood both the basic problem of human existence and its solution. Instead, they taught that “a human who seeks only to become a member of his next evolutionary kingdom may become a member of that kingdom if he completely overcomes all the aspects and influences of the human level providing he has found favor with a member of that next level who will direct him through his metamorphosis”’.[21]

This principally unoriginal brand of transcendence was the core dogma of Heaven’s Gate and it was also largely responsible, along with other culminating circumstances, for the ritual suicides of 39 believers.[22] Another factor which may have hastened their suicide, besides the near-to-earth passing of the comet (Hale-Bopp) the group believed to be trailed by their alien-saviours’ spaceship,[23] was the unexpected and faith-challenging death of Nettles, who died suddenly in 1985 of liver cancer,[24] which, according to the dogma of the group, was not supposed to have happened.[25] According to the biblical prophecy in the book of Revelation Nettles and Applewhite taught as part of the cult’s central dogma, these ‘Two Witnesses’, Nettles and Applewhite, were to be assassinated as a sign of the End Times.[26] Instead of viewing this event as a failure, the group rationalized it as a success. The members of Heaven’s Gate interpreted Nettles’ death as being the result of ‘the physical manifestation of the stress that existed “due to the gap between her Next Level mind and the vehicle’s [Nettles’ body] genetic capacity’.[27] Cowan and Bromley remark:

‘That is, through her own ongoing communion with the Next Level, Nettles’s mind had actually evolved to the point where her body could no longer function adequately as a container for it’.[28]

The father of ‘Cognitive Dissonance Theory’, Leon Festinger, based his social-psychological theory on his observations of a similar UFO cult, the Seekers.[29] Festinger developed the theory of cognitive dissonance as a result of a similar dissonance-producing event that occurred to the Seekers.[30] The central dogma of the Seekers, as dictated by their leader Marion Keech, was that the human race would be destroyed in a cataclysmic flood, and that the cult would be saved aboard alien spaceships.[31] When doomsday (December 21st, 1954) came and went without incident, some individuals abandoned the cult, yet a number of highly committed members chose to interpret the event not as a failure, but a success.[32] According to Festinger, the prediction made by the leader of the Seekers, that of the earth’s imminent destruction, became a ‘disconfirmed expectancy’ that caused dissonance between the cognitions, ‘the world is going to end’ and ‘the world did not end’.[33] The remaining members resolved their dissonance by accepting a new supplementary belief, and also by seeking reassurance from fellow believers who provided justification for their beliefs.[34] They rationalized that the world had been spared because of the faith of their group.[35] The adoption of the new supplementary belief allowed the members of the cult to reduce their cognitive dissonance by employing an ‘adaptational strategy’ which took the form of the aforementioned rationalization, which, in turn, preserved their core dogmas, i.e., that their leader had been telepathically communicating with aliens and that their group was specially chosen by these spacemen.[36] Like the Seekers, the members of Heaven’s Gate, whose core dogmas had been challenged by a dissonance-producing event, preserved them by adding a supplementary belief to their central dogma in order to resolve their cognitive dissonance and protect their egos via this psychological defence mechanism.[37]

Unlike Heaven’s Gate, the Branch Davidians’ core dogmas were not dictated by their leader David Koresh. As mentioned, their history reaches approximately 150 years into the past [38] and the dogmas of this group have developed over that time, under the influences of various leaders. The Branch Davidians transitioned through four distinct phases, with each phase being marked by different leaders and different cult names.[39] In their latest phase, the Branch Davidians did have additional dogmas dictated by their leader David Koresh. One of these dogmas was the belief that David Koresh, whose real name was Vernon Wayne Howell, was the next messiah who alone possessed the ability to unlock the ‘seven seals’ mentioned in the book of Revelation.[40] The other dogma unique to this phase of the Branch Davidians was the ‘New Light’ doctrine. Cowan and Bromley enunciate this doctrine in the following words:

‘Revelation 19:7 speaks of the “marriage of the Lamb,” and how “his wife hath made herself ready.” Based on his interpretation of this, rather than a purely spiritual salvation, Koresh taught that his messianic mission was to create a new lineage of God’s children, a new House of David that would ultimately reign over the new heaven and the new earth predicted at the end of Revelation. Though Koresh began taking other “spiritual wives” as early as 1987, this new doctrine revealed that he would be the messianic husband to all female members of the community and father divine offspring through them’.[41]

Despite the disconfirmation of the dogmas propagated by David Koresh, who is now deceased, the Branch Davidians continue to exist as a cult, proving, in similitude to Heaven’s Gate and the Seekers, that dogmas and deeply-held beliefs survive by way of dissonance-reducing psychological strategies. Similar dissonance-reducing strategies litter Christian history, from the rationalisations employed to mitigate the failed prophecies of Jesus’ imminent return,[42] to the advent of the science of geology that proved the earth was much older than the widely-accepted biblical chronology of James Ussher,[43] to Darwin’s theory of evolution, which completely undermined a literal interpretation of the creation account in the book of Genesis.[44]

ISOLATION

Isolation is a common strategy employed by religions and cults to control the physical and psychological environments of the believer. One may observe this isolation strategy within the Gospel of Luke, in which the anonymous author wrote: ‘If anyone comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters–yes, even their own life–such a person cannot be my disciple’.[45]

Both Heaven’s Gate and the Branch Davidians employed strict isolation as a means of controlling their members. Members of both cults lived in secluded locations – the Branch Davidians in the Mount Carmel Compound in Waco, Texas [46] and Heaven’s Gate members resided at a mansion in the Rancho Santa Fe district, twenty miles north of San Diego.[47] The reason for such isolation, as mentioned, is to control the cognitive influences that cult members encounter, and also, to ensure that new members are thoroughly indoctrinated/socialized, or re-socialized, in accordance with the cult’s unifying set of dogmas and beliefs. Discussing isolation, Breckler, Olsen and Wiggins say:

‘Cults try to bring recruits to locations that are removed from their familiar surroundings…These retreats give the cult complete control over the recruit’s environment, allowing extensive socialization procedures and significant interpersonal pressure to be applied. If someone does join a cult, he or she is almost always forced to move into a cult-controlled environment (e.g. a commune) and to sever all contact with non-cult friends and family’.[48]

DEPENDENCY

The members of Heaven’s Gate were obviously dependent on the cult for the satisfaction of their needs, for on the one hand, what greater expression of dependency on the cult is there than ending one’s life in devotion to its core beliefs, and on the other, the ‘Exist Statements’ of the members testify: ‘I am nothing without Ti [Nettles] and Do [Applewhite]’.[49] Further, the social networks developed in such an insular environment create dependency. Members come to rely exclusively on the support of fellow members, and the cult leaders in particular.[50] The same is true of the Branch Davidians, who lived in isolation from the outside world. Discussing the device of cult dependency as it relates to the Branch Davidians under David Koresh, who exploited his charismatic leadership to engage in unconventional sexual practices with young female members, Wright remarks: ‘Through effective resistance to the threat of institutionalization charismatic leaders may be able to render followers exclusively dependent upon them, eliminating constraints or inhibitions on their whims, leading to the possible emergence of unconventional sexual practices and violence’.[51]

Langone’s ‘Deception-Dependency-Dread’ (DDD) model proposes that cults like Heaven’s Gate and the Branch Davidians employ similar tactics to those used by Chinese communists in brainwashing American POWs during the Korean conflict.[52] However, according to Langone, due to the cult’s inability to forcibly isolate new members, they use deception to fool the member into believing that the group is somehow uniquely beneficial to the individual member.[53] Once they have persuaded the new member to willingly submit to the group and commit psychologically, the member becomes dependent on the psychological support of the group. Nowak, Vallacher and Miller note:

‘…commitment can influence behavior as much as do reciprocity, equity, responsibility, and other basic social rules and expectations (Kiesler, 1971). After people have committed themselves to an opinion or course of action, it is difficult for them to change their minds, recant, or otherwise fail to stay the course. Commitment does not derive its power solely from the anger and disappointment that breaking of a commitment would engender in others—although this certainly counts for something—but also from a basic desire to act consistently with one’s point of view. A commitment that is expressed publicly, whether in front of a crowd or to a single individual, is especially effective in locking in a person’s opinion or promise, making it resistant to change despite the availability of good reasons for reconsideration (cf. Deutsch & Gerard, 1955; Schlenker, 1980)’.[54]

According to Langone, the dependency cults acquire from members results in a dread of losing the psychological support of the group, which causes the individual to voluntarily forgo freedom of thought and independence of mind. Thus, the DDD model posits that cults use a three-pronged strategy for recruiting and retaining members – by acquiring psychologically coerced dependency and then relying on the dread of forfeiting the psychological support that the individual has become dependent upon.[55] It may be argued that in addition to Langone’s DDD model, the psychological drive for consistency works to further ensnare the prospective member, whose commitment works as a self-ensnaring tool.

BEHAVIOUR CONTROL

Life for the Heaven’s Gate members involved a strict routine, with tasks changing every twelve minutes.[56] The addition of uniforms was also another highly effective strategy employed by Heaven’s Gate to unify the members’ cognitions and behaviours. According to Balch, following the introduction of uniforms, ‘factionalism disappeared, conformity increased, and the defection rate dropped precipitously’.[57] The behaviour control that Nettles and Applewhite exerted over the cult culminated in the ritual suicide of 39 members, which, needless to say, represents the height of behaviour control.

David Koresh also gained substantial control over the members of the Branch Davidians. This resulted in Koresh achieving unfettered freedom to molest young female members and it even granted him free access to the wives of other male members.[58] The intense religious devotionalism instated by Koresh, along with the twice-daily bible studies that would last for hours, during which members would be forbidden from going to the toilet, demonstrates the acute behaviour control exercised by Koresh.[59] Further, as with Heaven’s Gate, there is no greater evidence of behaviour control than the group’s willingness to die for their beliefs, which, in the case of the Branch Davidians, manifested in the form of an “apocalyptic” armed response to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms.[60] Galanter sees Koresh’s behaviour control over his cult in terms of the monitoring function, which describes the influence exerted by collective beliefs and social cohesiveness.[61] Galanter also argues that the cult’s isolation from the outside world helped to protect the group’s ideology from outside incursions that in turn helped to solidify and intensify the cult’s shared beliefs, which gave Koresh greater power for behavioural control over his followers.[62]

GROUP LABELLED AS DEVIANT BY OUTSIDERS

Sociologists conceptualize deviance as being either formal or informal.[63] Informal deviance describes behaviours that violate customary norms,[64] whilst formal deviance describes behaviours that break laws or official rules.[65] Further, according to Becker’s theory of deviance, reaction is a primary element of deviance [66] – that is to say, ‘whether an act is deviant…depends on how other people react to it.’[67]

Whilst both Heaven’s Gate and the Branch Davidians were both labelled deviant by outsiders, it appears that prior to their facilitation of ritual suicide, Heaven’s Gate were merely deviant in an informal sense, whereas the Branch Davidians had, prior to their fire fight with federal authorities, engaged in illicit behaviours and illegal sexual acts, thereby constituting formal deviance. In their ‘Exit Interviews’ members of Heaven’s Gate describe how they had been labelled as deviant cult members, and how people had misunderstood them. They also emphatically pleaded with people to avoid listening to how they will inevitably be perceived by the media following their suicides, which further demonstrates that they knew they were going to be labelled as deviant.[68]

Similarly, in a self-recorded monologue, David Koresh described the harassment he and his cult received from the ATF, saying:

“…and I did not appreciate it and never will I appreciate somebody coming here with two helicopters…and pushing people around with guns. I’ll meet you at the doorstep any day”.[69]

Further, many of the media headlines about the siege in Waco reveal that this group was labelled as deviant, if not for their particular religious beliefs, for the fact that they were a cult.[70] Discussing the deviance of the ‘cult’, Stark and Bainbridge say: ‘The second form of deviant religious group is the cult. As we define them, cults are religious groups outside the conventional religious traditions of society. They may or may not impose strict demands on their adherents, but their primary form of religious deviance does not concern being too strict, but too different’.[71] It is interesting to note that when Christianity was in its early stages, prior to Constantine’s endorsement in the Fourth Century,[72] it was also labelled as a deviant religious group.[73] Aside from the works of early Christians who documented the occasional persecutions they suffered, there exists historical evidence that attests to the common perception amongst the citizens of the Roman Empire, who viewed Christianity as a deviant religion.[74] The primary deviance of Christianity in the ante-Nicene period was its reluctance to worship the emperor as a god, which, at the time, was considered both formal and informal deviance.[75]

It is therefore reasonable to argue that the predominant distinction between these two cults and the Christian religion, according to Pavlos’ definition, exists largely within discursive processes. Christianity is a religious group whose leader(s) formulated the group’s dogmas – they are, to varying degrees, isolated from the outside world socially and psychologically, as well as physically, if only whilst they perform their religious rituals. It is also possible to argue that the Christian household acts as a subsidiary of the Christian cult, maintaining the cultish isolation of members whilst they are not in church. Further, Christians are rendered dependent upon the dogmas of their religion for perceived survival and social acceptance amongst members of their group, and the doctrines of the religion combined with the social and psychological pressures inherent within their religious lives lead to behaviour control. However, such behaviour control may be argued to be far less acute than in cults whose members live in isolated compounds, but again, the religious family environment may mitigate such a distinction, to varying degrees.

CONCLUSION

If Pavlos’ definition of cult is applied to both Heaven’s Gate and the Branch Davidians, the term cult appears to be an accurate one. They were both religious groups – their leader(s) formulated the respective groups’ dogmas – they lived in isolation from the outside world – the members were dependent upon the support of the cult – the groups’ leaders exercised behavioural control over members of the cults – and both Heaven’s Gate and the Branch Davidians were labelled as deviant religious groups. All of these elements identified by Pavlos appear to work together to create an environment that causes individuals to forfeit control of their own thoughts and behaviours, and the social and psychological pressures that exist help to ensure the continuation of adherence, even in the face of events and information that disconfirm the cult’s dogmas.

Finally, each element of Pavlos’ definition of cult can be applied to the Christian religion, albeit in a looser fashion. Christianity is both an extrinsically and intrinsically identifiable religious group – its leader(s) did formulate the group’s dogmas – this religious group does exist in relative isolation from the outside world, although not to the same extent as cults like Heaven’s Gate and the Branch Davidians – Christians are dependent upon the group for social and psychological support – the group’s initial leader(s), along with those who have assumed that role within each of the extant denominations, assert control over the behaviour of Christians – and Christianity was viewed as deviant in the early stages of its development and it remains deviant in nations where Christians are a minority. Thus, it appears that there is very little difference between a cult and a religion, or at least the Christian religion. To conclude, the primary distinction between a socially acceptable religion and a deviant cult lies in discursive processes which determine whether a group should be defined as a religion or as a cult.

END NOTES

Debate: Sam Harris and William Lane Craig, Atheism vs Christianity (at 1 hour and 19 minutes), cited at: YouTube, accessed on 8th of April, 2016.

Andrew J. Pavlos, The Cult Experience, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982, p. 6.

William Bezdek, Groups, cited in: George Ritzer (ed.) and J. Michael Ryan (ed.), The Concise Encyclopedia of Sociology, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, 2011, p. 273.

David G. Bromley and Catherine Wessinger, Millennial Visions and Conflict with Society, cited in: Catherine Wessinger (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Millennialism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 202.

Steve Moyise (ed.), Studies in the Book of Revelation, Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2001, p. 22.

Stephen D. O’Leary, Arguing the Apocalypse: A Theory of Millennial Rhetoric, New York: Oxford University Press, 1994, p. 111.

Eugene V. Gallagher (ed.) W. Michael Ashcraft (ed.), Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America, London: Greenwood Press, 2006, p. 158.

James Alan Fox and Jack Levin, Extreme Killing: Understanding Serial and Mass Murder, 3rd Ed., Los Angeles: Sage Publications, Inc., 2015, p. 137.

Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley, Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015, p. 132.

John Burnett, Two Decades Later, Some Branch Davidians Still Believe, cited at: http://www.npr.org/2013/04/20/178063471/two-decades-later-some-branch-davidians-still-believe, accessed on 12th April, 2016.

George D. Chryssides (ed.), Heaven’s Gate: Postmodernity and Popular Culture in a Suicide Group, Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2011, p. 1.

Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley, Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015, pp. 143-144.

Ibid. p.147.

Ibid.

The Bible, Revelation 11:12, ‘The New International Version’.

Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley, Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015, p. 146.

George D. Chryssides (ed.), Heaven’s Gate: Postmodernity and Popular Culture in a Suicide Group, Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2011, p. 116.

Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley, Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015, p. 147.

Ibid. p. 146.

Ibid. p. 147; Karen L. King, What is Gnosticism?, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003, p. 120.

Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley, Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015, p. 147.

Robert W. Balch and David Taylor, Making Sense of the Heaven’s Gate Suicides, cited in: David Bromley (ed.) and J. Gordon Melton (ed.), Cults, Religion, and Violence, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 209.

Ibid. p. 104.

Ibid. p. 217.

Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley, Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015, p. 152.

The Bible, Revelation 11:7, ‘The New International Version’.

Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley, Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015, p. 152.

Ibid.

Joel Cooper, Cognitive Dissonance: 50 Years of a Classic Theory, Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2007, p. 5.

Ibid.

Leon Festinger, Henry W. Riecken and Stanley Schachter, When Prophecy Fails, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1956, p. 62.

Ibid. p. 169.

Ibid. p. 228.

Ibid.

Ibid. p. 169.

Ibid. p. 30.

Jeffrey S. Nevand, Essentials of Psychology: Concepts and Applications, 3rd Ed., Belmont: Wadsworth, 2012, p. 386.

Steve Moyise (ed.), Studies in the Book of Revelation, Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2001, p. 22.

Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley, Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015, p. 122.

pp. 123, 129; The Bible, Revelation 5-8, ‘The New International Version’.

Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley, Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015, p. 130.

The Bible, Matthew 10:23, 24:34; Mark 13:30, ‘The New International Version’.

Philip C. Almond, Adam and Eve in Seventeenth-Century Thought, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 86; Martina Kolbl-Ebert (ed.), Geology and Religion: A History of Harmony and Hostility, London: The Geological Society London, 2009, p. 159.

John A. Moore, From Genesis to Genetics: The Case of Evolution and Creationism, Berkley: University of California Press, 2002, p. 68.

The Bible, Luke 14:26, ‘New International Version’.

Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley, Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015, p. 136.

Ibid. p. 141.

Steven J. Breckler, James M. Olsen and Elizabeth C. Wiggins, Social Psychology Alive, Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth, 2006, p. 293.

Janja Lalich, Bounded Choice: True Believers and Charismatic Cults, Berkley: University of California Press, 2004, p. 224.

Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley, Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015, p. 150.

Stuart A. Wright (ed.), Armageddon in Waco: Critical Perspectives on the Branch Davidian Conflict, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995, p. 247.

Michael D. Langone, PhD, Clinical Update on Cults, ‘Psychiatric Times’ (July 1, 1996), p. 3, cited at: psychiatrictimes.com/printpdf/157697, accessed on 11th April, 2016.

Ibid.

Andrzej Nowak, Robin R. Vallacher, and Mandy E. Miller, Social Influence and Group Dynamics, cited in: Irving B. Weiner (ed.), Theodore Millon (ed.), and Melvin J. Lerner (ed.), Handbook of Psychology, Vol. 5: Personality and Social Psychology, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2003, p. 395.

Michael D. Langone, PhD, Clinical Update on Cults, ‘Psychiatric Times’ (July 1, 1996), p. 3, cited at: psychiatrictimes.com/printpdf/157697, accessed on 11th April, 2016.

Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley, Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015, p. 151.

Ibid. p. 152.

Clive Doyle, Catherine Wessinger and Matthew D. Wittme, A Journey to Waco: Autobiography of a Branch Davidian, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2012, p. 213; Timothy Miller (ed.), America’s Alternative Religions, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995, p. 155.

Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley, Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015, p. 128; Children of Waco Documentary, 10th August, 2009, cited at: YouTube, accessed on 12th April, 2016.

Stuart A. Wright (ed.), Armageddon in Waco: Critical Perspectives on the Branch Davidian Conflict, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995, p. 365.

Marc Galanter, Cults: Faith, Healing, and Coercion, 2nd Ed., New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, pp. 115, 170.

Ibid. p. 170.

Margaret L. Anderson & Howard E. Taylor, ‘Sociology: The Essentials, 7th’, Belmont, CA, 2013, p.144.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Howard S. Becker, ‘Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance’, New York, 1973, p. 9.

Ibid. p. 11.

Heaven’s Gate Exit Interviews, cited at: YouTube, accessed on 11th April, 2016.

David Koresh, David Koresh Tells the Truth About Waco, cited at: YouTube, accessed on 11th April, 2016.

Sam Howe Verhovek, 4 U.S. Agents Killed in Texas Shootout with Cult, The New York Times, cited at: http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/big/0228.html, accessed on 11th April, 2016; Negotiations with cult drag on; Released youngsters comforted, Dallas Morning News Archives, cited at: http://www.nationoftexas.com/waco/waco/www.public-action.com/SkyWriter/WacoMuseum/library/dallasmn.html, accessed on 11th April, 2016; Sue Anne Pressley, Waco Siege Ends in Dozens of Deaths as Cult Site Burns After FBI Assault, The Washington Post, April 20th, 1993, cited at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1993/04/20/waco-siege-ends-in-dozens-of-deaths-as-cult-site-burns-after-fbi-assault/57bee939-d20b-49b5-9a7e-77b722a10ea4/, accessed on 11th April, 2016.

Rodney Stark and William Sims Bainbridge, Religion, Deviance, and Social Control, New York: Routledge, 1996, p. 104.

Henry Chadwick, The Church in Ancient Society: From Galilee to Gregory the Great, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 187.

Donald G. Kyle, Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome, London: Routledge, 1998, p. 256; Bart D. Ehrman. From Jesus to Constantine: A History of Early Christianity, ‘Lecture 11: The Early Persecutions of the State’, The Teaching Company, 2004; Eusebius, History of the Church: Book 7, Chapter 30:19-20; cited in: Philip Schaff. NPNF2-01. Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine, New York: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890, p. 507.

Ibid.

Bart D. Ehrman. From Jesus to Constantine: A History of Early Christianity, ‘Lecture 11: The Early Persecutions of the State’, The Teaching Company, 2004.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

RELIGIOUS TEXTS

The Bible, Revelation 11:12, ‘The New International Version’.

The Bible, Revelation 11:7, ‘The New International Version’.

The Bible, Revelation 5-8, ‘The New International Version’.

The Bible, Matthew 10:23, 24:34; Mark 13:30, ‘The New International Version’.

The Bible, Luke 14:26, ‘New International Version’.

PRIMARY SOURCES

Eusebius, History of the Church: Book 7, Chapter 30:19-20; cited in: Schaff, Philip. NPNF2-01. Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine, New York: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890.

Koresh, David, David Koresh Tells the Truth About Waco, cited at: YouTube, accessed on 11th April, 2016.

Negotiations with cult drag on; Released youngsters comforted, Dallas Morning News Archives, cited at: http://www.nationoftexas.com/waco/waco/www.public-action.com/SkyWriter/WacoMuseum/library/dallasmn.html, accessed on 11th April, 2016.

Pressley, Sue Anne, Waco Siege Ends in Dozens of Deaths as Cult Site Burns After FBI Assault, The Washington Post, April 20th, 1993, cited at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1993/04/20/waco-siege-ends-in-dozens-of-deaths-as-cult-site-burns-after-fbi-assault/57bee939-d20b-49b5-9a7e-77b722a10ea4/, accessed on 11th April, 2016.

Verhovek, Sam Howe, 4 U.S. Agents Killed in Texas Shootout with Cult, The New York Times, cited at: http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/big/0228.html, accessed on 11th April, 2016.

SECONDARY SOURCES

Almond, Philip C., Adam and Eve in Seventeenth-Century Thought, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Anderson, Margaret L. & Taylor, Howard E., ‘Sociology: The Essentials, 7th Ed.’, Belmont, CA, 2013.

Balch, Robert W. and Taylor, David, Making Sense of the Heaven’s Gate Suicides, cited in: David Bromley (ed.) and J. Gordon Melton (ed.), Cults, Religion, and Violence, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Becker, Howard S., ‘Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance’, New York, 1973.

Bezdek, William, Groups, cited in: George Ritzer (ed.) and Ryan, J. Michael (ed.), The Concise Encyclopedia of Sociology, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, 2011.

Breckler, Steven J., Olsen, James M. and Wiggins, Elizabeth C., Social Psychology Alive, Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth, 2006.

Bromley, David G. and Wessinger, Catherine, Millennial Visions and Conflict with Society, cited in: Catherine Wessinger (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Millennialism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Burnett, John, Two Decades Later, Some Branch Davidians Still Believe, cited at: http://www.npr.org/2013/04/20/178063471/two-decades-later-some-branch-davidians-still-believe, accessed on 12th April, 2016.

Chadwick, Henry, The Church in Ancient Society: From Galilee to Gregory the Great, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Chryssides, George D. (ed.), Heaven’s Gate: Postmodernity and Popular Culture in a Suicide Group, Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2011.

Cooper, Joel, Cognitive Dissonance: 50 Years of a Classic Theory, Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2007.

Cowan, Douglas E. and Bromley, David G., Cults and New Religions: A Brief History, 2nd Ed., Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2015.

Doyle, Clive, Wessinger, Catherine and Wittme, Matthew D., A Journey to Waco: Autobiography of a Branch Davidian, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2012.

Ehrman, Bart D., From Jesus to Constantine: A History of Early Christianity, ‘Lecture 11: The Early Persecutions of the State’, The Teaching Company, 2004.

Festinger, Leon, Riecken, Henry W. and Schachter, Stanley, When Prophecy Fails, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1956.

Fox, James Alan and Levin, Jack, Extreme Killing: Understanding Serial and Mass Murder, 3rd Ed., Los Angeles: Sage Publications, Inc., 2015.

Galanter, Marc, Cults: Faith, Healing, and Coercion, 2nd Ed., New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Gallagher, Eugene V., (ed.) Ashcraft, W. Michael (ed.), Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America, London: Greenwood Press, 2006.

King, Karen L., What is Gnosticism?, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003.

Kolbl-Ebert, Martina (ed.), Geology and Religion: A History of Harmony and Hostility, London: The Geological Society London, 2009.

Kyle, Donald G., Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome, London: Routledge, 1998.

Lalich, Janja, Bounded Choice: True Believers and Charismatic Cults, Berkley: University of California Press, 2004.

Langone, Michael, Clinical Update on Cults, ‘Psychiatric Times’ (July 1, 1996), cited at: www.psychiatrictimes.com/printpdf/157697, accessed on 11th April, 2016.

Miller, Timothy (ed.), America’s Alternative Religions, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995.

Moore, John A., From Genesis to Genetics: The Case of Evolution and Creationism, Berkley: University of California Press, 2002.

Moyise, Steve (ed.), Studies in the Book of Revelation, Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2001.

Nevand, Jeffrey S., Essentials of Psychology: Concepts and Applications, 3rd Ed., Belmont: Wadsworth, 2012.

Nowak, Andrzej, Vallacher, Robin R. and Miller, Mandy E., Social Influence and Group Dynamics, cited in: Weiner, Iriving B. (ed.), Millon, Theodore (ed.), and Lerner, Melvin J. (ed.), Handbook of Psychology, Vol. 5: Personality and Social Psychology, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2003.

O’Leary, Stephen D., Arguing the Apocalypse: A Theory of Millennial Rhetoric, New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Pavlos, Andrew J., The Cult Experience, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982.

Stark, Rodney and Bainbridge, William Sims, Religion, Deviance, and Social Control, New York: Routledge, 1996.

Wright, Stuart (ed.), Armageddon in Waco: Critical Perspectives on the Branch Davidian Conflict, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.