Ancient Sumerian Art and Architecture – Kings, Gods and the True Purpose of Organized Religion

"The more you know about the past, the better prepared you are for the future." ~Theodore Roosevelt

INTRODUCTION

‘Every work of art causes the receiver to enter into a certain kind of relationship both with him who produced, or is producing, the art, and with all those who, simultaneously, previously, or subsequently, receive the same artistic impression’[1] ~Leo Tolstoy

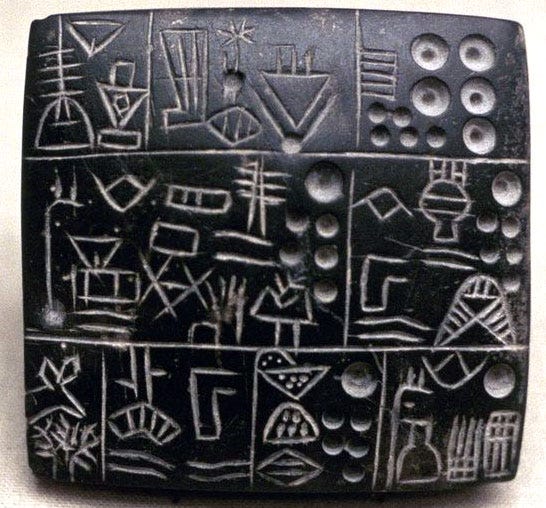

Is it possible for us to enter into a kind of relationship with the artists and architects of ancient Sumer and receive, through their artistic expressions, impressions of the perceived relationship between Sumerian rulers and their gods? This essay will argue that such a relationship, although fraught with caveats and reservations, is not only possible, but fruitful. By examining the layout of the cities, the sacred spaces, palaces, stelae, reliefs, artefacts and primary literary sources, it is possible to gain some insight into this religious aspect of the Sumerian psyche. Once the evidence has been examined and assessed with the assistance of secondary source material, it will be concluded that the art and architecture of ancient Sumer, specifically from around the middle of the Uruk Period (3000 BCE approx.)[2] to the end of the Ur III Period (2004 BCE approx.),[3] paints a picture of kings who were believed to have been the mediators between heaven and earth, the lynch pins keeping city-states from suffering the wrath of temperamental gods, the primary servants of the gods, and in some rare cases, gods themselves.

THE SUMERIAN CITY AS ART - URUK

How a city is planned and laid out may be seen as the artistic expression of those who take part in its planning, building and development. In Charles Landry’s The Art of City Making, he contends:

‘City-makers are artists of the highest order because they have a grasp of all the arts concerned with city-making’.[4]

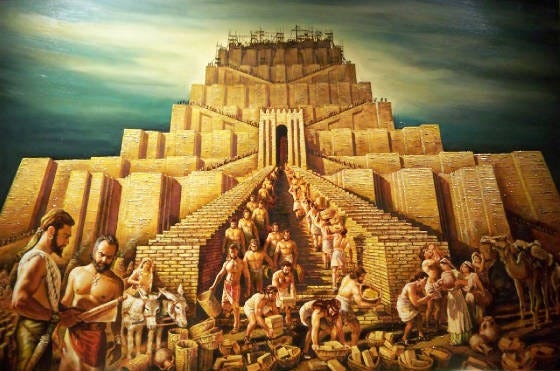

This was certainly true of the builders, designers and developers of the city of Uruk. Uruk was the first great city of the ancient world.[5] By 3200 BCE it had expanded to an impressive 250 ha.[6] The city eventually reached an amazing 550 ha by the early part of the Early Dynastic Period (ED)[7], housing approximately 80,000 inhabitants.[8] Toward the beginning of the third millennium BCE the city’s walls were 4-5 meters thick [9] and six meters high,[10] forming a protective circuit that ran approximately 9.5 kilometres around this city [11] that had as its centrepiece a grandiose, elevated temple that scraped the very bottom of the heavens, or so might have been the impression its grandeur imprinted upon the mind of the ancient observer. After continued and layered development [12] the main temple of the Anu District eventually became the famous multi-tiered Anu Ziggurat, which could be seen from miles away. Hans Nissen has calculated that the construction of this grand ziggurat required the efforts of 1,500 labourers working ten hours a day continuously over a five-year period. [13]

One can scarcely imagine the awe this temple-jewelled city must have inspired in the mind of the ancient Sumerian wandering the southern plains Mesopotamia – who – having come across it for the first time might have thought; this city must be the residence of a great and powerful god, and its king must be a mighty man, a lugal! [14] And we might forgive this ancient Sumerian for thinking this way, for nothing like this colossal urban complex had ever been created prior to the construction and gradual development of Uruk.

Using Tolstoy’s relationship concept, we should ask, what were the urban planners and successive developers of Uruk trying to express with their design? And what does their design tell us about the relationship between Sumerian rulers and their gods? The layout of a city reveals a lot about its inhabitants. If, for example, the largest, most ostentatious, and most central building in the city is a religious temple and next to it is positioned an opulent royal palace, as was the case in the ancient city of Uruk, then it can be safely deduced that city life probably centred around the temple and the palace, and more specifically, around both the monarchy and religion of the city. It also demonstrates that the rulers and the gods lived together in the same part of the city. These facts imply two things: Firstly, that the focal point of the religion, the god(s), must have been of utmost importance to the social and political lives of the people. And secondly, the king, who in earlier times was the priest (Sum. ensi), [15] must have been closely associated with the patron god(s) of the city. Van De Mieroop confirms the significance of the gods and rulers to the ancient Sumerians, saying:

‘They [the gods] were ‘domesticated’; their cults were enshrined in a temple in the city. When the king attempted to promote the fertility of the land, he did not go out to the fields to perform rituals, but visited the goddess Inanna in her temple. The gods rarely left their cities, and, if they did, it was a cause for great concern.’ [16]

Not only has Van De Mieroop confirmed the central importance of the gods to the people of Uruk and Sumerian city-states in general, but he has hinted at one of the crucial aspects of the relationship between the rulers and their gods. The king was believed to have been a divinely appointed ambassador who mediated between the gods and their mortal servants. The priestly role of intercessor between the unwashed masses and the divine is a concept that has been a staple of theistic religions down throughout human history.

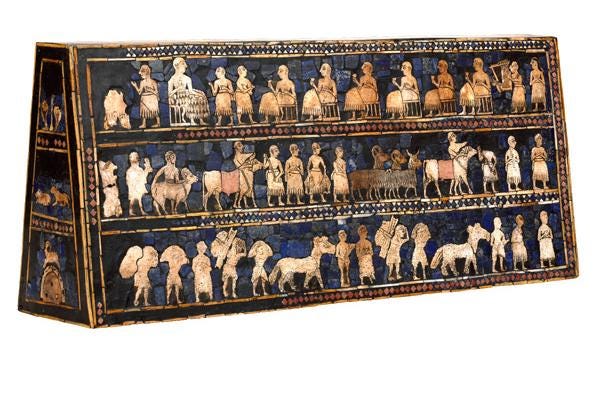

THE STANDARD OF UR

The king as mediator is reiterated by an examination of the Standard of Ur, which is a wooden trapezoidal box inlaid with mosaic scenes of war and peace, excavated by the British archaeologist Leonard Wooley in 1928 from the royal tomb of Queen Puabi, in what used to be the ancient Sumerian city of Ur.[17] According to McDonald and a number of other scholars,[18] the two sides of the standard could be representing the two sides of kingship: the role of the king as a ruler in wartime and his role as a mediator between the gods and the people.[19] This finding confirms what has been gleaned from the artistic expression of the planners of Uruk, who, in accommodating the dual role of the ruler, built their royal palace in the sacred and walled Eanna District.[20]

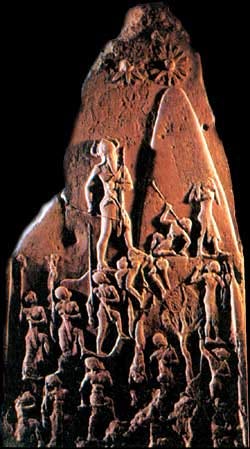

THE STELE OF THE VULTURES

A similar duality is found on the Stele of the Vultures. This stele dates to ED III (2600-2350 BCE) and, as with the Standard of Ur, one side depicts a battle, or preparations for a battle, and the other side portrays the positive outcome, which, in this case, is attributed to the patron deity of Lagash, Ningirsu.[21] Crawford describes this stele in the following words:

‘The stele commemorates the victory of Eannatum of Lagash over the neighbouring city of Umma and shows Eannatum leading his victorious army over the corpses of his enemies, while vultures pick at their severed heads…On the reverse of the stele the god of battle, Ningirsu, is shown holding a net containing the enemies of Lagash.’[22]

THE EPIC OF GILGAMESH - THE ART OF POETRY

Tolstoy includes poetry in his definition of art,[23] hence, it is permissible to draw upon another piece of Sumerian art, the poetic Epic of Gilgamesh, from which the role of the king and his relationship to the gods can be brought into sharper focus. This epic poem relates the legendary adventures of a legendary king of Uruk, Gilgamesh, whom the Sumerian King List names as the successor of Dumuzi,[24] and whom historians cautiously agree ruled sometime between 2800 and 2500 BCE.[25] The prologue of this poem sings:

‘He had the wall of Uruk built, the sheepfold

Of holiest Eanna, the pure treasury.

See its wall, which is like a copper band,

Survey its battlements, which nobody else can

match,

Take the threshold, which is from time immemorial,

Approach Eanna, the home of Ishtar,

Which no future king nor any man will ever match!

Go up on to the wall of Uruk and walk around!

Inspect the foundation platform and scrutinize the

Brickwork…Three square miles and the open ground comprise

Uruk’.[26]

From this piece of art we see that the role of the king was to build the city, the sacred temple, and the protective walls, which, along with the flamboyant temple, was one of the primary hallmarks of the Sumerian city. Thus, the role of the king was to oversee the building of the city and the house of the patron deity.

THE PERFORATED RELIEF OF UR-NANSHE

This aspect of the king’s role is further evinced by the relief-carved stone plaque of Ur-Nanshe, the founder of the first dynasty of Lagash (2500 BCE, approx.),[27] which shows the king presiding over the construction of a temple, probably that of Ningirsu, the patron deity of Lagash,[28] and carrying on his head some of the foundation bricks.[29] The accompanying inscription reads:

“Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash, son of Gunidu, built the temple of Ningirsu; he built the temple of Nanshe; he built Apsubanda.”[30]

Returning briefly to the Epic of Gilgamesh, this piece of art paints a somewhat rare picture of Sumerian kingship. The poem reads:

‘Two-thirds of him was divine, and one-third mortal’.[31]

The concept of the divine king is also present on the above mentioned Stele of the Vultures, which is accompanied by the following inscription:

‘Ningirsu implanted the seed of Eannatum in womb of Ninhursaga bore him. Over Eannatum Ninhursaga rejoiced; Inanna took him on (her) arm and named him “Worthy of the Eanna of Inanna of Ibgal”.[32]

THE RARE DEIFICATION OF SUMERIAN KINGS

Generally speaking, Sumerian rulers were viewed as nothing more than mortals, unlike Egyptian kings (Gk. pharaohs).[33] However, in a handful of instances Sumerian rulers appear to have undergone an apotheosis, as was the case with Gilgamesh and Eannatum. Frankfort, though, offers a possible caveat for Eannatum’s alleged divinity and he also cautions Sumerologists to avoid the error of conflating symbolic language with literalistic interpretations of what was communicated by such kings and their biographers, saying:

‘The text [inscription on the Stele of the Vultures] may then have a ritual or symbolic meaning which escapes us. As a mere guess we might suggest that it refers, not to the actual birth of Eannatum, but to his ritual “birth” as a god fit to be Inanna’s bridegroom’…However that may be, the numerous other texts in which Mesopotamian kings are called the “sons” of gods or goddesses do not imply that they are divine’.[34]

Whether or not the rulers were believed to have been actually divine is an issue for ongoing debate, however, given the amount of textual and archaeological evidence for the occasional deification of Sumerian kings, it may be argued that in some cases kings were believed to have been divine – yet, in all cases kings were believed to be divinely appointed.[35]

THE VICTORY STELE OF NARAM-SIN

Another example of a deified ruler comes to us from an ancient stele dated to around 2250 BCE.[36] The Victory Stele of Naram-Sin depicts the deified King Naram-Sin’s victory over the people of the Zagros Mountains known as the Lullubi.[37] The stele illustrates Naram-Sin ascending the Zagros Mountains and defeating his enemies, who, along with his men, are half his size. He is positioned beneath what appears to be solar orbs (possibly representing the sun-god Shamash) and the people, perhaps reiterating the role of king as intercessor between mortals and gods, and also possibly reflecting the belief that the gods assist kings in battle who serve them well; but what’s most interesting about this stele is that Naram-Sin is shown wearing a helmet with horns, which was an exclusively divine motif.[38]

CONCLUSION

By entering into a relationship with the artists and architects of ancient Sumer, we have been able to gain some cautious insight into the perceived relationship between Sumerian rulers and their gods. From an examination of the layout of the city of Uruk it can be seen that the artists who designed and continually redesigned this first great city believed that the kings and the gods should reside in close proximity to one another, revealing the dual role of the ruler, who was both a secular authority figure and a religious leader – a divine intercessor, appointed by the gods. The architects of Uruk also communicate the importance they placed upon their patron god(s), by building them ostentatious living quarters that could be seen from afar, and that oversaw the daily life of the urbanites of Uruk.

The various artefacts, reliefs and monuments also reveal that the ancient Sumerians viewed their kings as divinely appointed rulers who were, in some cases, divine. They believed their rulers’ responsibility was first and foremost to the patron god(s) of the city, and to mediate on the citizens’ behalf to ensure the ongoing welfare of those who resided within the city walls. Given all that we have learned from the artists of ancient Sumer, is it not fair to say that art is one of the great immortalizers? Through this medium we may enter into a kind of relationship with those who lived thousands of years ago. We are, through the medium of art, afforded the opportunity to cautiously psychoanalyze people whose brains have become but dust, but whose minds, in large part, live on within their artistic expressions. And most importantly, what does this relationship tell us about the origins and true purpose of organized religion? I think Book IV of Aristotle’s Politics has one probable answer to this question:

‘Also he [the tyrant] should appear to be particularly earnest in the service of the Gods; for if men think that a ruler is religious and has a reverence for the Gods, they are less afraid of suffering injustice at his hands, and they are less disposed to conspire against him, because they believe him to have the very Gods fighting on his side.’[39]

END NOTES

Leo Tolstoy, What is Art?, cited at: http://web.csulb.edu/~jvancamp/361r14.html, accessed on 05 Dec. 2015.

Harriet Crawford, Sumer and the Sumerians, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 25.

Tonia M. Sharlach, Provincial Taxation and the Ur III State, Leiden: Brill, 2004, p. 1.

Charles Landry, The Art of City Making, London: Earthscan, 2006, p. 420.

Mario Liverani, Uruk: The First City, (trans. Zainab Bahrani & Marc Van De Mieroop), London: Equinox Publiishing Inc., 1998, pp. x, 2; Ben Derudder (Ed.), Michael Hoyler (Ed.), Peter J. Taylor (Ed.), Frank Witlox (Ed.), International Handbook of Globalization and World Cities, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2012, p. 12.

Augusta McMahon, Mesopotamia, Sumer, and Akkad, in: Professor Deborah M. Pearsall (Ed), Encyclopedia of Archaeology, Vol. 2: B-M, San Diego: Elsevier-Academic Press, 2008, 855.

Jane R. McIntosh, Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives, Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005, 185.

Ben Derudder (Ed.), Michael Hoyler (Ed.), Peter J. Taylor (Ed.), Frank Witlox (Ed.), International Handbook of Globalization and World Cities, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2012, p. 12.

Jane R. McIntosh, Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives, Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005, 185.

Michael R.T. Dumper & Bruce E. Stanley (Ed), Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia, Santa Barbara: CLIO-ABC, 2007, 384.

Jane R. McIntosh, Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives, Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005, 185.

Stephen Bertman, Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003, 192.

Roger Matthews, The Archaeology of Mesopotamia: Theories and Approaches, London: Routledge, 2003, 110.

The Sumerian epithet lugal was reserved for kings and slave owners, and literally translates as “great man”: Henri Frankfort, Kingship and the Gods: A Study of Ancient Near Eastern Religion as the Integration of Society and Nature, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948, 218.

Ibid. p. 221.

Marc Van De Mieroop, The Ancient Mesopotamian City, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 216.

Professor Diana K. McDonald, 30 Masterpieces of the Ancient World, Lecture 4: The Standard of Ur – Role of the King, The Teaching Company, 2013.

Richard L. Zettler (Ed.), Lee Horne (Ed.), Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1998, 47.

Professor Diana K. McDonald, 30 Masterpieces of the Ancient World, Lecture 4: The Standard of Ur – Role of the King, The Teaching Company, 2013.

Bernard Wailes (Ed.), Craft Specialization and Social Evolution: In Memory of V. Gordan Childe, Philadelphia: The University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1996, p. 33.

Susan Pollock, Ancient Mesopotamia: The Eden That Never Was, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999, 184.

Harriet Crawford, Sumer and the Sumerians, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 165.

Leo Tolstoy, What is Art?, cited at: http://web.csulb.edu/~jvancamp/361r14.html, accessed on 05 Dec. 2015.

Samuel Noah Kramer, The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963, p. 45.

Stephanie Dalley, Myths from Mesopotamia, Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, 40.

Gilgamesh, Tablet I, cited in: Ibid. p. 50.

E.S. Edwards, C.J. Gadd, N.G.L. Hammond, The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol 1.2, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971, p. 116.

Perforated Relief of King Ur-Nanshe, Department of Near Eastern Antiquities: Mesopotamia, Louvre Museum, Paris, cited at: http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/perforated-relief-king-ur-nanshe, accessed on, 10 Dec. 2015.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Gilgamesh, Tablet I, cited in: Ibid. p. 51.

Henri Frankfort, Kingship and the Gods: A Study of Ancient Near Eastern Religion as the Integration of Society and Nature, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948, 301.

Ibid. p. 6.

Ibid. p. 301.

Stephanie Dalley, Myths from Mesopotamia, Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 49; Geoff Emberling, Mesopotamian Cities and Urban Process, 3500–1600 BCE, in: Norman Yoffee, The Cambridge World History, Vol. 3: Early Cities in Comparative Perspective, 4000 BCE-1200 CE, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 253.

Professor Diana K. McDonald, 30 Masterpieces of the Ancient World, Lecture 7: Victory Stela of Naram-Sin of Akkad, The Teaching Company, 2013.

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, Department of Near Eastern Antiquities: Mesopotamia, Louvre Museum, Paris, cited at: http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/victory-stele-naram-sin, accessed on, 10 Dec. 2015.

Kristian Kristiansen, Thomas B. Larson, The Rise of Bronze Age Society: Travels, Transmissions and Transformations, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 63.

Aristotle, Politics, (trans. Benjamin Jowett), Kitchener, Ontario: Batoche Books, 1999, p. 136.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

PRIMARY HISTORICAL SOURCES AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL ARTEFACTS

The Epic of Gilgamesh, cited in: Stephanie, Myths from Mesopotamia, Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989.

Perforated Relief of King Ur-Nanshe, Department of Near Eastern Antiquities: Mesopotamia, Louvre Museum, Paris, cited at: http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/perforated-relief-king-ur-nanshe, accessed on, 10 Dec. 2015.

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, Department of Near Eastern Antiquities: Mesopotamia, Louvre Museum, Paris, cited at: http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/victory-stele-naram-sin, accessed on, 10 Dec. 2015.

SECONDARY SOURCES

Aristotle, Politics, (trans. Benjamin Jowett), Kitchener, Ontario: Batoche Books, 1999.

Bertman, Stephan, Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Crawford, Harriet, Sumer and the Sumerians, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Dalley, Stephanie, Myths from Mesopotamia, Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989.

Derudder, Ben (Ed.), Hoyler, Michael, (Ed.), Taylor, Peter J., (Ed.), Witlox, Frank, (Ed.), International Handbook of Globalization and World Cities, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2012.

Edwards, I.E.S.,Gadd, C.J., Hammond, N.G.L., The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol 1.2, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971.

Emberling, Geoff, Mesopotamian Cities and Urban Process, 3500–1600 BCE, in: Yoffee, Norman, The Cambridge World History, Vol. 3: Early Cities in Comparative Perspective, 4000 BCE-1200 CE, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Frankfort, Henri, Kingship and the Gods: A Study of Ancient Near Eastern Religion as the Integration of Society and Nature, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948.

Kramer, Samuel Noah, The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963.

Kristiansen, Kristian, Larson, Thomas B., The Rise of Bronze Age Society: Travels, Transmissions and Transformations, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Landry, Charles, The Art of City Making, London: Earthscan, 2006.

Liverani, Mario, Uruk: The First City, (trans. Zainab Bahrani & Marc Van De Mieroop), London: Equinox Publiishing Inc., 1998.

Matthews, Roger, The Archaeology of Mesopotamia: Theories and Approaches, London: Routledge, 2003.

McDonald, Diana K., 30 Masterpieces of the Ancient World, Lecture 4: The Standard of Ur – Role of the King, The Teaching Company, 2013.

McIntosh, Jane R., Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives, Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005.

McMahon, Augusta, Mesopotamia, Sumer, and Akkad, in: Professor Deborah M. Pearsall (Ed), Encyclopedia of Archaeology, Vol. 2: B-M, San Diego: Elsevier-Academic Press, 2008.

Pollock, Susan, Ancient Mesopotamia: The Eden That Never Was, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Sharlach, Tonia M., Provincial Taxation and the Ur III State, Leiden: Brill, 2004.

Tolstoy, Leo What is Art?, cited at: http://web.csulb.edu/~jvancamp/361r14.html, accessed on 05 Dec. 2015.

Van De Mieroop, Marc, The Ancient Mesopotamian City, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Wailes, Bernard, (Ed.), Craft Specialization and Social Evolution: In Memory of V. Gordan Childe, Philadelphia: The University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1996.

Zettler, Richard L. (Ed.), Horne, Lee (Ed.), Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1998.